It investigates in a wide-ranging and systematic fashion a foundational but under-considered factor in the history and culture of the Vikings in England. For example: the word skǫr means ‘a male haircut’ but is feminine other feminine nouns include elli ‘old age,’ bók ‘book,’ fjǫðr ‘feather,’ saga ‘tale.’ Some masculine nouns are bragr ‘poetry,’ matr ‘food,’ steinn ‘stone,’ kærleikr ‘love.’ Neuter nouns include hjarta ‘heart,’ land ‘land,’ þing ‘parliament,’ fen ‘marsh or bog.This is the first ever book-length study for the nature and significance of the linguistic contact between speakers of Old Norse and Old English in Viking Age England. For example, the neuter noun barn (‘child’) remains neuter whether the child is a ‘he’ or a ‘she.’ Many nouns referring to abstract concepts and objects have genders that bear no relationship to the word itself. But keep in mind that sex is not a sure indicator of gender. If the noun denotes a living being, its gender often matches the being’s sex, for example, faðir ‘father’ (m) and móðir ‘mother’ (f). For example, many masculine nouns, such as maðr ‘man person’ and sonr ‘son,’ have the ending ‐r in the nominative case. The gender of a noun or pronoun can often be determined by looking at its set of case endings. GenderĪll nouns and pronouns in Old Norse belong to one of three genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. In most instances, the subject of a sentence is in the nominative case, the direct object is in the accusative case, the indirect object is in the dative, and the possessor (of something) is in the genitive. There are four cases in Old Norse: nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive.

CaseĪll nouns in Old Norse decline that is, they take endings indicating the noun’s case and role in the sentence.

When translating Old Norse, one needs to be able to distinguish differing endings to ensure meaning. It is worth noting that modern English has dropped most of its endings (inflections), and for this reason English is only marginally an inflected language. Endings are traditionally called ‘inflections,’ a term coming from Latin. In particular, Old Norse nouns, pronouns, and adjectives have different endings depending on their gender, case, and number when conveying differing roles in a sentence (subject, object, etc.). Old Norse is an ‘inflected language,’ meaning that parts of many words change in order to distinguish between grammatical categories. The letter ð (upper case, Ð) is called ‘eth’ and pronounced like ‘th’ in the English word ‘breathe’ or Othin (Óðinn), often spelled ‘Odin’ in English. Thorns are used at the beginning of words. The letter þ (upper case, Þ) is called ‘thorn’ and pronounced like ‘th’ in the English word ‘thought’ or the name of the god Thor (Þórr). The letters c, q, and are occasionally found in manuscripts but have not been adopted into the standardized alphabet.

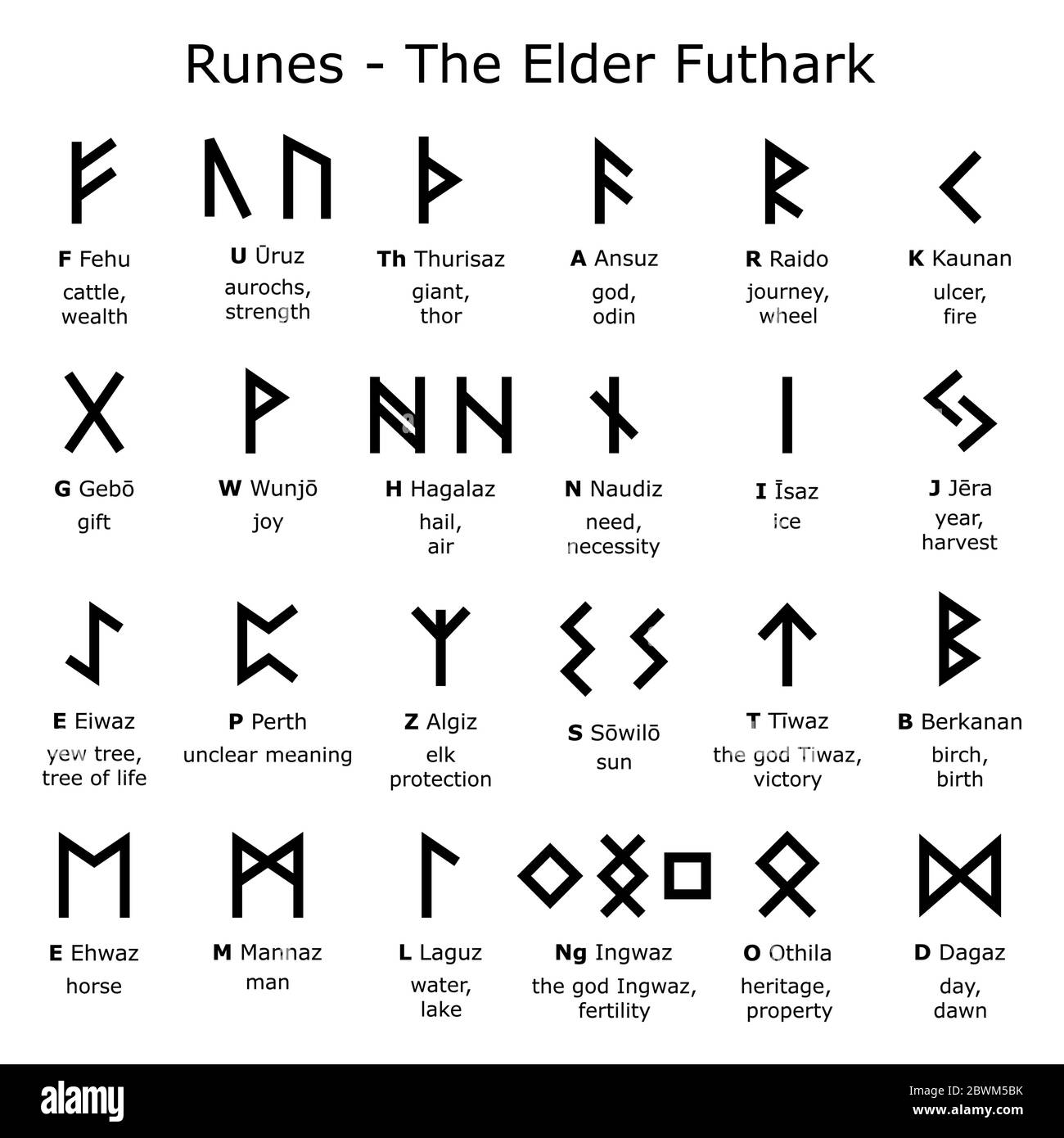

The long vowels æ, œ, ø and ǫ (umlauted a, which becomes modern ö) are listed at the end of the Icelandic alphabet. In the Old Norse/Icelandic alphabet, long vowels are distinguished from short vowels by an acute accent (for example, long é and short e). Overall, the spelling differences between Old and Modern Icelandic are minor. In most instances, this book retains the original medieval distinction. Modern Icelandic has also lost the distinction between æ and œ and employs æ for both letters. This book maintains the distinction between ǫ and ø. This current edition employs ǫ, but ö is found when a Modern Icelandic term or name is used. The first edition of Viking Language 1, generally employed ö. The Old Norse vowels ǫ and ø coalesced in the medieval period into the single vowel ö, which is still used in Modern Icelandic. Scholars addressed this issue more than a century ago by adopting a standardized Old Norse/Icelandic spelling and alphabetic order. Old Norse writers, whether they wrote runes or manuscripts, did not follow a standardized spelling. From this source, Icelanders may have learned the letters þ (‘thorn,’ uppercase Þ) and ð (‘eth,’ uppercase Ð). The Latin alphabet adopted by the Icelanders in the eleventh century was probably modeled on Anglo‐Saxon writing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)